The Heritage Era of Panoramas

Panorama Paintings

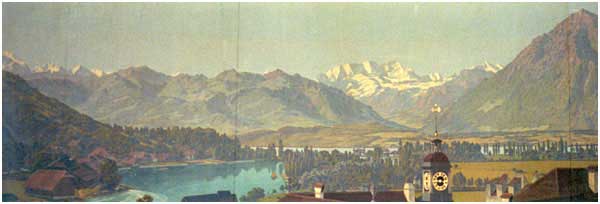

Wocher's Panorama of Thun, Switzerland

Pictured above is the oldest panorama in existence, which remains on view to the public. A lovely skiing town beside the Thunersee, the landscape of Thun and its township was immortalized in canvas by Marquard Wocher in 1814. The detailed painting, somewhat smaller than later panoramas, showed the rooftops and intricate spires of the town, while leaving plenty of space for the dramatic mountains in the distance for which Switzerland is known. Many of the man-made landmarks depicted in 1814 still exist, such as the central clock tower in the town square. These paintings inspired a sense of wonderment at the accuracy of the panoramic painting itself, as well as a feeling of pride for people admiring the beauty of their own town.

Panorama paintings often served as a form of pseudo-travel and offered escape into the exotic realms which so captured the imagination of 19th-century citizens. Subject matter of panoramas included Roman Ruins, the Nile in Cairo, the jungle depths of the Congo, the explosion of Mount Vesuvius, and the well-groomed grounds of Versailles.

Religious subject matter offered another popular theme in 19th-century panoramas. These works were often accompanied by detailed guides so visitors could reconstruct the particulars of significant religious episodes and find relevant persons within the narrative matter of the painting. Later on, remaining panoramas often added an audio component which narrated the religious story depicted to awestruck visitors. The above image shows The Panorama of the Crucifixion of Christ which exists in the pilgrimage town of Einsiedeln, Switzerland. This panorama proved to be so popular and significant in the modern era that, when the painting and rotunda burned entirely to the ground in 1960, the entire site was replaced with an exact replica and re-opened to the public a mere two years later.

Panorama Rotundas

Massively elegant, these striking panorama rotundas advertise the sensational treasures housed within and lure visitors to their doorstep, matching the spectacle created by the magnificent paintings inside. These monumental buildings were, in the panorama's heyday, built to accommodate paintings of up to 360 feet in circumference [110 meters] and 45 feet high [14 meters]. Incorporated into the design of the building was the lighting of the panorama painting inside. Lit by indirect natural light from above, this necessary technical feature also heightened the feeling of faux-reality experienced within the panorama, as changes in sunlight or the effects of moving clouds would be projected upon the panoramic painting and three-dimensional terrain.

As was typical for buildings of the time period, the panorama rotunda's greatest foe was fire. These large wooden structures, often filled with old, dry brush used as part of the faux terrain, were extremely susceptible to fire and could disappear in flames almost instantly. Many panorama rotunda structures were never intended to be long-term buildings, some just quickly built with cheap materials for a world's fair or temporary exhibit run. Over the years, many of the panorama rotundas have been replaced with more durable structures so as to preserve the panoramic phenomenon for all to experience as time marches on.

Wroclaw, Poland

Panorama of Raclawice

Pleven, Bulgaria

Pleven Epopee 1877

Ying Xiong Mountain, Jinan, China

Jinan Campaign Storming of Heavily Fortified Positions in the City